Hierzu existiert auch eine deutsche Version: Behinderung und chronische Krankeit während der Pandemie

Questo documento ha una versione in italiano: Disabilità e malattie croniche nella pandemia

A history of struggle against the disposability of disabled lives

People with disabilities or chronic illnesses have been long subject to a denial of care. No matter where we are, we have had to contend with the shortfalls in medical treatment, adaptation of built environment, access to assistive technologies, personalised assistance and many other unmet requirements. However, we have equally been subject to imposition of care. We have had to wrestle our autonomy away from familial overprotection, forced institutionalisation and segregation in specialised institutions. There is a long history of our communities organising and struggling to overcome this double – objective and subjective – disablement.

Social model of disability and disability rights movement

A critical juncture in this history arrived in the 60s and 70s, as the inchoate disability rights movement started to level a critique against the then-dominant medical model of disability. The medical model,1 which replaced the earlier eugenics model, viewed disability primarily as an individual affliction that had to be addressed through medical treatment and socialised through specialised institutions. However, the medical model was reductive as it failed to comprehend the individual affliction in its social context and thus has perpetuated the exclusion of our communities from the most aspects of social life.

From this critique emerged an integrative, social model of disability,2 which considers physical, sensory, cognitive or psychological impairments as they appear in the social world of physical barriers, prejudicial attitudes, invisibility and ability-prioritising sphere of labour. Institutional, cultural and environmental factors, modelled around the norm of able-bodiedness, converge to limit people with disabilities in achieving their different capabilities and aspirations. It is this process of social disablement, and not the impairment itself, that defines disability.

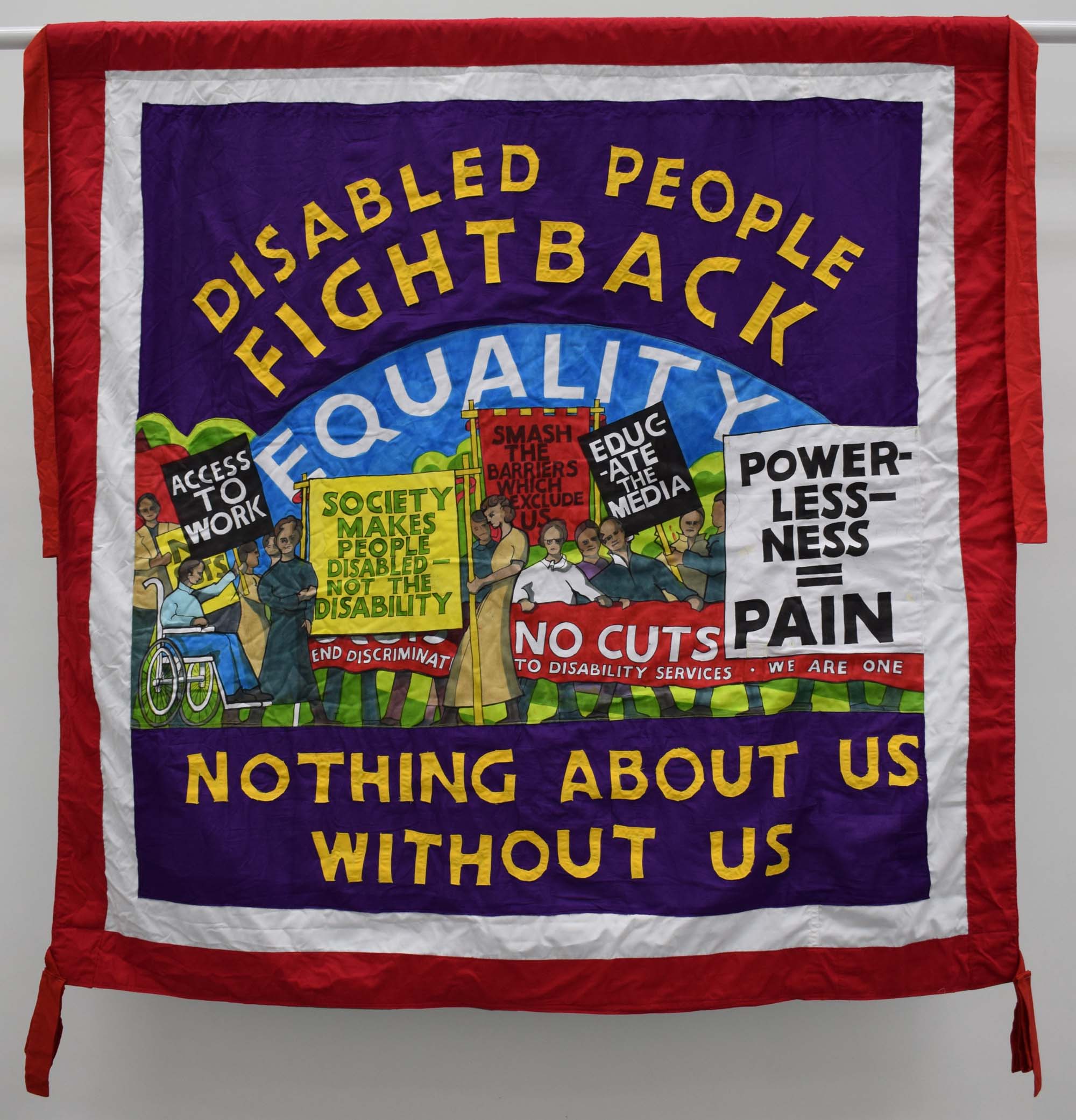

From this enlarged understanding of disability, the disability rights movement in the 1970s initiated a cycle of protests, campaigns and direct actions, inspired and supported by the larger civil justice and labour movements, that contested the power of economic interest and paternalistic institutions to demand an unconditional recognition of disability rights and creation of inclusive institutional settings. People with disabilities had a right to individually and collectively define their own requirements and a right to pursue independent living.

Radical model of disability and continuity of struggle

While the social model initially had emphasised the structural exclusion and relations of power, through its successes over the next two decades, it increasingly narrowed its focus on disability as isolated from other forms of structural oppression. It also largely ignored the relations of (inter-)dependence that continued to be constitutive not only of the lives of many people with disabilities who required care and assistance but also of the entire able-bodied population in various forms throughout their lives. From these shortcomings, in the 1990s emerged the radical model of disability that rested on the understanding of disability as one of many different ways of being, foregrounding positive identification, self-empowerment, intersectionality and queering, cripping and madding of the ableist society.

However, achieving disability rights, formulated under the social model of disability, still remains a challenge even in the highly progressive and affluent contexts. Ultimately, this has always depended and will continue to depend on our continued capacity to organise our in/interdependent living and mobilise against the discrimination, paternalism and neglect. This painful awareness that nothing is achieved that cannot be lost is enshrined in our slogan that also works as a warning: “Nothing About Us Without Us!”.

Therefore, after a history of struggle, it should be clear, particularly to public health authorities and political decision-makers, that the disability community and the allied communities of people with chronic illnesses, obesity or bodies broken by exploitation, poverty or unemployment will not sit still while others make the decisions in the current pandemic that risk making our lives disposable again.

The pandemic and the threat to our lives

World Health Organisation3 estimates that around 15% of the global population lives with some form of disability, many of whom are additionally afflicted by secondary conditions, co-morbidities, earlier ageing and premature death. These afflictions are compounded by inadequate medical care, lacking social protection, unemployment, poverty and social isolation.

All these factors become factors of additional risk in the situations of epidemics, as these social determinants of health inequality create conditions for faster transmission and higher morbidity and mortality.4 With the outbreak of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, where morbidity and mortality are particularly high among those with underlying health conditions, people with disabilities or chronic illnesses now face a situation of extreme vulnerability. Most of us are best advised to avoid getting infected to start with.

However, that vulnerability can become amplified by the public health and political decisions in the pandemic in several ways:

A perpetuation of invisibility in public health guidance

First, public health measures, protocols and messaging frequently do not include adequate consideration of specific requirements of people with disabilities or chronic illnesses.5 In a situation of significant danger to our lives we are again made irrelevant and invisible.

For instance, in public guidance, we are typically lumped together as “other at-risk groups”. While the disability and chronic illness often come with the prospect of limited mobility and living a life largely confined to home, many among us depend on regular professional or family assistance and therefore cannot simply maintain distance and isolate as advised by the public health guidance. Given that care workers typically assist more than one person and work in more than one institution, forced to do so by low wages and precarious work arrangements, they are themselves both at risk of getting infected and transmitting the infection.

For such reasons, public health protocols, guidance, messaging and hotlines need to be put in place that will be specifically aimed at reducing the risk of infection for people with disabilities and assistants. Also, social protection measures need to be put in place to have additional assistants at hand, to guarantee that all assistant work – professional or not – during the pandemic is paid and that assistants can get a sick pay in the case they get infected.6

Furthermore, the sense that there is a continuity of making disability and chronic illness invisible in inadequate public health measures and messaging is only reinforced by the contrast we can observe in what societies are willing to do to create accommodations for able-bodied people who now have to live and work confined mostly to their homes and thus depend on the essential work of others. Under different circumstances, for our lives, those accommodations are simply not to be had.

Availability of critical medical supplies and medical treatment

Second, people with disabilities or chronic illnesses frequently require oxygen tanks, ventilators and protective equipment such as masks and gloves. However, at present these are in short supply and a failure to include among priority receivers people with disabilities or chronic illnesses when securing these supplies might aggravate existing health conditions and increase vulnerability.

Vulnerability is also increased for those among us who need to visit hospitals for medical treatments such as dialysis or therapy for critical acute conditions. Hospitals have to plan in advance such emergency capacity and make arrangements to reduce the risks of transmission to disabled out-patients, which might become difficult if an outbreak overwhelms the capacities of hospitals.

Most at risk are those among us, however, who are in nursing homes or boarding schools. These institutions should have procedures in place and be subject to stricter supervision, particularly if they are privately managed, to avoid cases of massive neglect and defection of nursing staff as has reportedly happened in some nursing homes in Spain.

De-prioritising and triage

Third, as a sudden spike in the need for beds, ventilators or medical staff threatens to overwhelm the healthcare system, public health authorities and hospitals are forced to make hard decisions on allocation of insufficient resources between patients requiring critical care. On principle, those who have smaller chances of recovery given their underlying health conditions or their clinical outlook are de-prioritised. As the harrowing situation in Lombardy has demonstrated, doctors have no other choice but to follow such guidance when doing triage whom to place on ventilator support and whom to let die.7 The danger here is that people with disabilities or chronic illnesses are implicitly de-prioritised. In fact, in some U.S. states, such as Alabama and Tennessee, critical care plans explicitly de-prioritise people with an intellectual disability or spinal muscular atrophy, assuming their lives are worth less.8

People with disabilities or chronic illnesses are thus de-prioritised and made disposable in two ways: first because of their greater needs requirement when it comes to medical supplies and treatment – and then when it comes to critical care because of their underlying health conditions. For these reasons, the American Association of People with Disabilities has sent a letter to Congress demanding “a statutory prohibition on the rationing of scarce medical resources on the basis of anticipated or demonstrated resource-intensity needs.” 8 Otherwise, the discrimination and disposability of lives will be perpetuated through the measures that are designed to save lives in the first place.

“Nothing About Us Without Us!”

As the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic spreads, the disability and chronic illness communities are mobilising and organising, knowing fully well that the decision-makers and institutions are quick to neglect their prior commitments to disability rights. Our response is not confined to actions of governments and institutions. We are contributing to broader solidarity networks organising collective assistance and mutual aid, providing guidance for people with disabilities9, chronic illnesses10 or conditions such as obesity11.

However, given the dangerous consequences of neglect, it is essential that we mobilise to demand from public health authorities to include us in the decision-making processes that will ultimately reflect on our chances of survival

References

Health Inequalities and Infectious Disease Epidemics: A Challenge for Global Health Security ↩︎

‘The Cripples Will Save You’: A Critical Coronavirus Message from a Disability Activist ↩︎

People with a disability are more likely to die from coronavirus – but we can reduce this risk ↩︎

COVID-19 Resources for the Disability Community and COVID-19 Disability Community Preparedness Resources (U.S. Based) ↩︎

Fat-Assed Prepper Survival Tips for Preparing for a Coronavirus Quarantine ↩︎